and to the last pulse in my veins i shall resist

political prisoners, mycelium, palestinian youth movement & other things underground

well well well, what the fuck is going on

i can’t concentrate. on sitting down to write this, on Survivor re-runs, on sleeping. and no, it’s not ADHD, i think it’s more to do with the sharp clarity of looking hell in the face day after day. the diabolical experience of witnessing mass torture and mass awakening and mass dissociation. of existing somewhere in between all three. the words hell and evil don’t feel strong enough. i mock myself as i say them, outside the pub, in the group chat. though truth be told i’ve always seen hell everywhere, or felt it at least. hell is the workplace, the institution, the destruction of nature, the capital fucking letter. when i was a social worker in the US, trying badly to secure the most vulnerable and most deserving people measly fucking crumbs of support via the health care system i described it as feeling like the devil’s secretary and i wasn't even working for the devil but aren’t we all? aren’t we fucking all.

one of the many things I never quite got about religion, even as a child, was all the hell chat. you mean to say………. another one…..??? worse than this!!!????? don’t think so love. and yet it also makes sense to me that we would need to believe that there is a justice metered out somewhere, somehow, because there is no such thing here on earth. no justice other than the forehead kisses of forgiveness and the open palms of apology we work to give our friends and lovers and c o m m u n i t y and ourselves tho let’s be real - ain’t those still hard-won. these days i find solace in telling myself that god will deal with what i cannot. and i try not to feel guilty for only calling on Him (let’s go for a classic Him) when on airplanes and for vengeance. it is what it is.

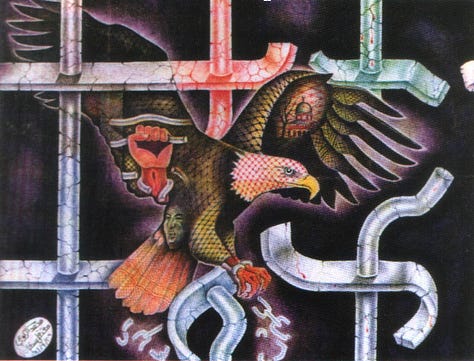

if hell is not here on earth then its fire is. you can’t tell me hellfire is not here. it has risen, it is rising, it powers Israeli weaponry which is to say it powers these bastard imperial nations so many of us call “home?” and it burns where a zionist’s soul would be, translucent in its heat, barely a flame at all. hell’s fire forged the first coin, the first shackle. but there’s fire in heaven too. and it lights the path to liberation. heaven’s fire bathes us in cleansing smoke, it burns the indigenous forest to keep it abundant, it carries the martyrs and those who choose to give their bodies to it, to their final resting place. peace, peace, peace be on their souls. i was not expecting to write about fire two months in a row but when it wants us to pay attention, we do.

recently i went to see Fungi: Web of Life at the imax kind of coz it’s narrated by bjork and also coz i’m trying to get over my secret phobia of fungi especially since i finally started properly microdosing (remember this attempt? lmao) and to be honest I didn't go in expecting a decolonial framework for the future of human-fungi interaction from this film which was good because…. yeah. however i was also not expecting most of the screen time to be taken up by a tall white man in an anorak walking aimlessly around various rainforests and looking under rocks which in 3D honestly felt violating to my spirit so yeah, a thumbs down from me. however it was nice, as it always is, to be reminded of all that lies beneath. the creatures of depth and mystery that still somehow surround us on this planet.

i’m gonna go ahead and assume that being gay, most of my readership know what mycelium is. but for those who don’t (you are still enough) it’s like a huge fucking underground structure of kind of gross (sorry) rooty threads which produce fungi, the fruiting body of which sometimes become the mushrooms we see. and for all the mushrooms we see, there is like, WAY more mycelium. the film said something about if you stretched all the mycelium out in a line it would reach the other side of the Milky Way galaxy or something which - how do they know - but also, cool!

the point is, these hidden threads are masters of communication, equal facilitation of resources, diversity, survival, decomposition and therefore life. they like, invented mutual aid and the more scientists try to colonise - i mean learn about them, the more answers and remedies they are finding for the bleak future humankind has set itself up for, almost as if they knew it was coming. we don’t deserve their lessons, and we probably won’t get them due to a mix of rapid deforestation and also the fact that the people now in charge of these more-than-human negotiations of ancestral wisdom simply do not have the soul to hear the gospel. mycelium delivers messages to trees. why not just keep it that way.

as we left the cinema i was like well that was depressing blah blah blah to my friend Samirah and she was like i found it hopeful! it made me feel held! and then i was like you know what, let’s go with that. so now i found it hopeful and feel held which is awesome. (toxic positivity is literally all we have left, get into it) but really though when the time lapse footage of these lil brainless myceliums stopped making me feel queasy and i could actually sit with the magnitude of it all i did feel awed at all that happens underground. this winter has been hard on me, but thinking of roots has grounded me many times. as a depressive i feel such gratitude for soil and roots and the way they whisper to me over and over again; in your own time, in your own time. you will rise again in your own time. you don’t have to be seen to exist.

the earth too guides us through hellfire.

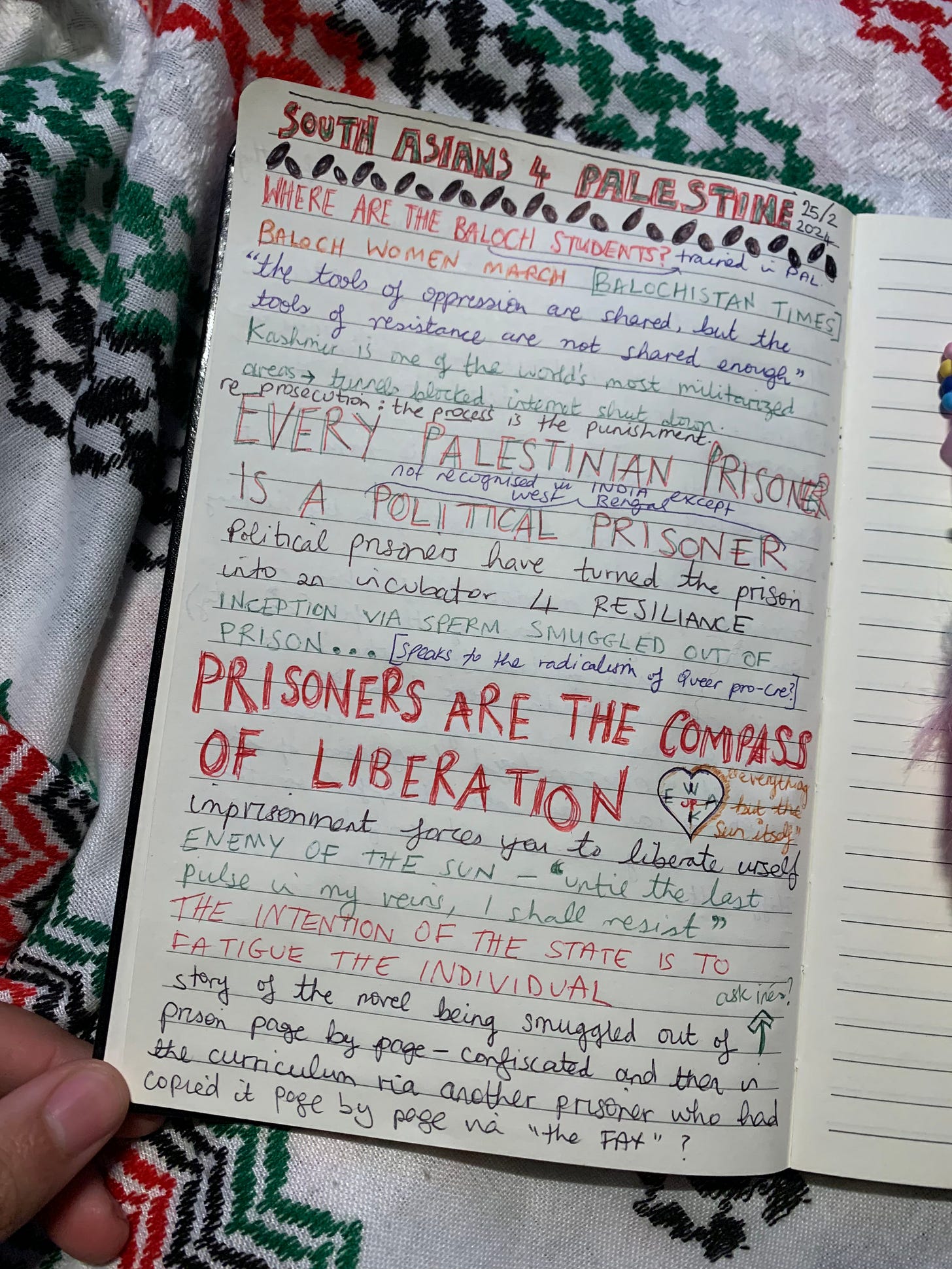

later that day i went to a teach-in organised by South Asians 4 Palestine and it was fucking harrowing and also made me very happy to be alive, to be in that room with those people in that moment. the focus of the event was on political prisoners, and the ways in which occupation, fascism and incarceration in Kashmir and across South Asia relates to the genocide in Palestine and vice versa. listening to the stories of political prisoners, i felt for a moment that we attendees might actually be mushrooms sitting along logs in the wood wide web, learning about the networks of care beneath us, who feed us, and fight for us, in ways we can’t imagine let alone see.

it made me think of the tunnels under Gaza, now flooded with salt water and US military and the secrets of genocide. it made me think of new york, and how when i am there i try to sit close to Mad people. how one time in 2017 on the subway an elder Black woman was speaking out the same phrase repeatedly, to no-one, to everyone, to herself. i leant in to catch what it was and she was saying "what is true is that we are watching genocide and no-body's complaining".

at the teach-in, we learnt the story of Wisam Rafeedie a Palestinian writer and resister who while kept in Israeli jail under administrative detention wrote a novel. this novel was smuggled out by other Palestinian prisoners, page by page, via an elaborate network called The Fax. but ultimately the scheme was disrupted and the book destroyed by prison guards. at some point later Wisam saw his book on a curriculum (sorry I am paraphrasing, watch the video below and have an informed person tell you the story lol) and realised that the book had actually made it out the prison via another prisoner who had copied out each page of the novel word for word when it reached his cell. i cried…

when I was reading up on Wisam Rafeedie I came across this excerpt of a letter he sent from prison which felt important:

It is clear that I, like all administrative detainees, am not the only one who is ‘punished’ (not ‘detained’) but my family is also. Likewise, I have not been punished just once but endure a whole series of punishments: when I am stuffed inside an airless room, with fifteen other detainees with one toilet and one bath; when I cannot find suitable conditions to read and write; when I cannot visit family and friends; when I cannot reassure myself as to the health of my mother and brothers and sisters. Thus the title of the law should be changed from the Law of Administrative Detention to the Law of Punishments of the Administrative Detainee! Once again I’m back to sarcasm! Like other administrative detainees, I use it as a response to the hardships of life, the repressiveness of administrative detention and the inhumanity of the conditions of detention.

If my sarcasm becomes a spur for more Israeli acts against administrative detention and a spur for more and more effort to bring down this unjust policy..., then my sarcasm will have fulfilled an additional task other than expressing my own inner resentment.

the book has just been translated into english and is being released right now here’s the link if like me you would like to read!! book club?

i want to leave you with this speech that was made by an amazing representative of Palestinian Youth Movement Britain, Inés. The Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM) is an independent, transnational, grassroots, base-building movement of Palestinian and Arab youth in exile as a result of the ongoing Zionist colonisation and occupation of their homelands. PYM brings together youth across political, cultural, and social backgrounds to organise towards a better future, characterised by freedom and justice, the Right of Return for all refugees, and towards the dismantling of Zionism.

Inés kindly shared it with me so i can share it with you. they spoke with a soft and brilliant clarity that empowered, taught and soothed me at the same time and i wanted you to also have a chance to bathe in these words and this knowledge and in this reverence of political prisoners, the legacy of indefinite detention used in occupied Palestine and so many other places to invisibalize, brutalise and break, and in all the other things we can’t see. this is the good fire.

The question of prisoners is crucial, and I am glad South Asians for Palestine have chosen to raise it today. As Rafeef Ziadah pointed out in a video from the recent Workers in Palestine day school that many of you may have seen, the topic of Palestinian prisoners is rarely addressed in the solidarity movement here. But it is central to this current war, and it is central to Palestinians – and no family is untouched by the Zionist entity’s prison system.

The first important point is that every Palestinian prisoner is a political prisoner. Palestinian prisoners are intentionally targeted for their resistance to Zionism and their leadership in the Palestinian struggle for national liberation. This is clear when we understand that the main function of Zionist prisons is to attempt to quell Palestinian resistance. Incarceration is a Zionist strategy to isolate Palestinians fighting for freedom from the rest of Palestinian society and from their land. It is used as a tool to suppress national leadership, to break apart families and the social fabric, and to collectively punish Palestinians by destroying any political or cultural organisation within Palestinian society. Every time we witness mounting Palestinian resistance, whether organised or popular, the carceral system escalates its operations and gets more brutal. This is evident in the mass arrests and kidnappings we have witnessed in the West Bank and Gaza since October 7th, as well as the intensification of horrific conditions and treatment inside prisons which have led to the martyrdom of nine prisoners in the last four months.

Before the establishment of the Zionist state, prisons were used under the British as a way to crush resistance to both Zionism and British colonialism. The use of imprisonment and detention as a tool of collective punishment became especially common during the 1936 to 1939 Great Arab revolution, a peasant uprising against British imperial rule and Zionist colonisation. It was the British that introduced administrative detention, which is used today as a legal tool through which Zionist military courts can indefinitely renew Palestinians’ prison sentences with no trial or charge.

But despite the Zionist entity’s intentions to use prisons to destroy the spirit and dignity of Palestinians and Palestinian revolutionaries, political prisoners have turned the prison into an incubator of national consciousness, political education, leadership, and resistance. Palestinian political prisoners exemplify steadfastness (or sumud), and sumud takes on an institutionalised form within prisons. The Palestinian Prisoners Movement has transformed prisons into spaces of intense academic and cultural education. They have classes and curriculums, all created by prisoners themselves, and hundreds of prisoners have obtained high school diplomas, bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees and even doctorates while behind bars. Many prisoners have published studies, novels, and poetry from inside.

And so a common slogan is ‘they can imprison our bodies but not our minds’. But Palestinian political prisoners also push the limits of bodily autonomy inside prisons, and the political prisoner struggle has long been characterized by the practice of the hunger strike. Since 1967, Palestinians have carried out hunger strikes either on an individual, group, or mass level, with demands including proper medical care, an end to solitary confinement, an end to administrative detention, and access to education – it is through such hunger strikes that the education I described has become possible. There is also a tradition of inventive methods being used to combat the isolation of imprisonment, from Walid Daqqah and his wife conceiving their child through smuggling sperm out of prison to the smuggling of ‘capsules’ – pieces of paper folded, wrapped, and passed around or swallowed. It is through this practice of capsule smuggling that the political prisoner Wisam Rafeedie’s novel was shared between prisoners and eventually with people outside; it has recently been translated into English by the PYM and I can talk more about this later if people are interested.

So, it is important to stress the political agency of prisoners, in opposition to constructions of the figure of the prisoner as a powerless, passive subject. As I mentioned, it is the leadership of the Palestinian movement who are targeted for imprisonment, but many of those who do not enter prison as a leader become leaders inside. Prisons are their own political organism and are sites where unity triumphs over factionalism – when someone is interred, their leadership rank is respected in prison regardless of their faction. In times of division on the streets, the prisoners' movement has come out demanding that the unity in prison be reflected outside, and it is the leaders in prison who when released are the most senior on the Palestinian street.

This leads me to the relationship of political prisoners to the broader struggle. This relationship can be summed up in the common refrain that prisoners are the ‘compass of our struggle’. They are in the most intimate daily confrontation with Zionism, on the frontlines of the fight for self-determination, and they are at the forefront of the Palestinian national liberation movement. This is no surprise because prisoners also serve as a representation of a nation in captivity: we can conceive of the Palestinian condition itself as one of imprisonment. It is common to hear Gaza referred to as an open-air prison, and we can extend this analysis further. All of historic Palestine under Zionist occupation is a carceral state. It manifests differently in the West Bank, in Gaza, in 48 borders (what is referred to as Israel) – and even in exile – but in all cases it is underpinned by the carceral logic of Zionism.

The relationship between the prison and the wider Palestinian population is elaborated by Walid Daqqah in his essay Searing Consciousness. Daqqah is one of the longest held detainees; he has been in prison since 1986 and is still being detained despite already completing his sentence. He was recently diagnosed with cancer and it is clear that the Zionist prison authorities want to continue his slow death. In Searing Consciousness, he writes that the prison system targets “the material and moral infrastructure of resistance”. Crucially, he argues that the targeting of the Palestinian collective psyche is experimented with inside prison before being exported outside. He thus sees the prison as a testing ground and a microcosm of Palestinian society at large, affirming our insistence that prisoners must be a compass for liberation.

Given this, we must think about how we can support Palestinian political prisoners in our efforts here. First, we can support political prisoners through the demands we are making as we take action and exert political pressure. Whilst our most immediate concern is calling for a ceasefire, we must not lose sight of our broader demands – one of which is the release of all Palestinian political prisoners. It is our duty to build consciousness around the Palestinian prisoners’ struggle and to organise for their freedom, and to understand that our other demands – like lifting the siege on Gaza and ending the 75-year occupation – are also anti-carceral demands. We can also amplify the actions taken by prisoners like hunger strikes, and the demands that accompany them.

Finally, we must center prisoners as a guide, following their teachings of the importance of unity and knowledge/political education, and their unwavering steadfastness. We must honour them by following their example and refusing to be intimidated or defeated, no matter the repression we are met with. The senses of freedom through resistance achieved by Palestinian political prisoners from within Zionist prisons can teach us something about freedom outside. Jean Genet, who was himself in and out of prison during his life, remarked in Prisoner of Love (his memoir of his time spent with the Black Panthers in the US and with Palestinians in Jordan and Lebanon) on the condition of the prisoner who, deprived of freedom, is proud of fixing himself up with freedom within prison.

He writes: “Freedom in freedom; freedom in constraint. The first is given, the second wrested from yourself… [People] may also value the proscription [ie imprisonment] that makes you find liberty within yourself.” This sentiment reflects the remarks of Walid Daqqah who writes from his cell, in his own words, “in the hopes of freeing the prison from within me”. Genet’s contrast between the given freedom outside prison and the wrested freedom within it is complicated and expanded by the Palestinian context, and by Daqqah’s observation that the unfreedom of prison is a microcosm of what lies outside its walls. Palestinian prisoners, with their steadfast insistence on building consciousness, are not only wresting freedom from and for themselves; they are, in the process, teaching us all that we must follow their lead and transform our conditions, seek and find freedom, beside them.

That Genet’s encounters with the Palestinian resistance and the Black Panthers are contained within the same pages is no surprise. A key lesson of the Palestinian Prisoner’s Movement – as well as unity and knowledge which I have discussed – is the importance of internationalism, and I want to end on this note of internationalism as we go on to discuss the linkages between prisoner struggles in different contexts. Leaders of the Palestinian prisoner movement often pen letters of comradery and solidarity with causes elsewhere in the world. Little encapsulates the linkages between struggles better than the story of the poem ‘Enemy in the Sun’. The poem was found in the cell of George Jackson, the leader and martyr of the Black Panthers, after his death in prison, and it was published under his name. Unknown to his comrades who found it penned in his notebook, the poem was written by the Palestinian poet and political prisoner Samih Al Qassem – a Palestinian resisting Zionist colonisation and brutality. The fact that the Black Panthers could not discern if the story in the poem was the story of George Jackson or the Palestinian people goes to show that all of our struggles are deeply connected. I will leave you with the words of Samih Al Qassem in that same poem:

I may―if you wish―lose my livelihood

I may sell my shirt and bed.

I may work as a stone cutter,

A street sweeper, a porter.

I may clean your stores

Or rummage your garbage for food.

I may lie down hungry,

O enemy of the sun,

But

I shall not compromise

And to the last pulse in my veins

I shall resist.

any money made from my substack this month will be donated to Palestinian Youth Movement Britain. blessed be the paid subscribers <3

tysm

never not brilliant